Double-flash

- Illusory Flashing Visual Percept Induced by Sound

L. B. Shams, Y. Kamitani, S. Shimojo

Purpose: Various studies have shown the modulation of perceived intensity, detectability, spatial and temporal localization of visual stimuli by an accessory auditory stimulus (AAS). AAS is an auditory stimulus that is presented in close temporal proximity of the visual stimulus and which is not to be responded to. We investigated whether the visual percept itself can be modified by such auditory stimulation.

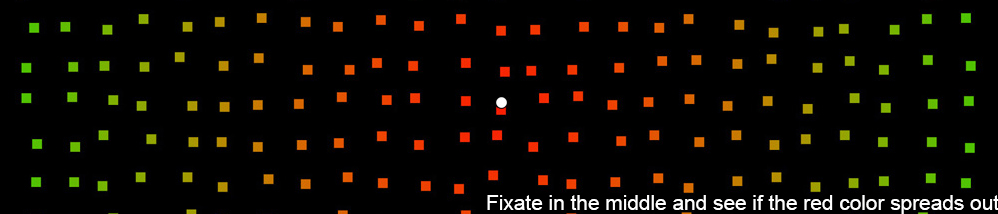

Methods: In each trial, a disk is flashed for 13.3ms in the center of a computer screen (where the subjects fixate). In one condition, the flash is accompanied by a brief sound stimulus which consists of 1 to 3 beeps (with the number and pitch of the beeps randomized across trials), and in another condition, the visual stimulus is not accompanied by any auditory signal. The subjects’ task is to judge the number of flashes displayed on the screen in each trial.

Results: Although the visual stimulus is identical across all trials (a single flash), the percept of the visual stimulus varies drastically across trials. Subjects perceive the single flash as more than one flash in the condition where the flash is accompanied with auditory beeps, and not otherwise. In other words, the sound beeps induce the perception of "visual beeps." Moreover, the number of flashes perceived in each trial is correlated significantly with the number of beeps in the same trial. A single flash is reported in trials with single beep. The results are robust to many parameters namely the duration of the visual flash, the flashing visual pattern, the size of the visual pattern, etc. and spatial concordance between the auditory and visual stimuli is not necessary.

Conclusion: AAS can alter the visual percept qualitatively and significantly. The observed illusory flash effect does not seem to be due to general attentional enhancement caused by auditory stimulation, as there is no illusory flash elicited by a single beep. The illusion does not appear to be a result of eye movements, as the effect is stronger with shorter flash durations, persists with very large disk size, and degrades with decrease in disk contrast. The observed illusion (as well as its non-requirement of spatial concordance between the auditory and visual stimuli) can be explained based on prior behavioral findings relating the audio-visual sensory interactions.

- When sound affects vision:

Audiovisual attention and visual motion perception

K. Watanabe , S. Shimojo

Two identical visual targets moving across each other can be perceived either to bounce off or to stream through each other (Metzger, 1934). A brief sound at the moment the targets coincide biases perception toward bouncing (Sekuler et al., 1997). By using this ambiguous motion display and the bounce-inducing effect, we determined an interaction range for audiovisual event classification.

We found that a sound can bias the perception even when it was presented from 250-ms before to 150-ms after the visual coincidence, suggesting that the temporal interaction range is rather long. Likewise, the spatial interaction range is wide: With a separation up to 30-deg of visual angle between the sound and the visual display, the bounce-inducing effect was virtually unchanged. Subsequent experiments showed that the bounce-inducing effect depends on auditory context.

For example, the effect was attenuated when the simultaneous sound was embedded in other identical sounds (auditory flankers) with an sound-onset-asynchrony of about 300 ms. The attenuation occurred only when the simultaneous sound and auditory flankers has similar acoustic characteristics and the simultaneous sound was not salient. These results suggest that there is an aspect of auditory-grouping (saliency-assigning) processes which is context-sensitive and can be utilized by the visual system for ambiguity solving.

Based on the finding that the saliency of sound is crucial for the bounce-inducing effect, I hypothesized that an allocation process of crossmodal attention may be involved in this audiovisual effect. If the motion mechanism responsible for the dominance of the streaming percept requires attention and a salient sound attracts attention automatically, the bounce-inducing effect would results. This was confirmed by the experiments where a sudden visual flash (exogenous attention distraction) or an additional task (endogenous attention distraction) at the moment of the visual coincidence also enhanced the bouncing percept.

Thus the present study shows (1) the spatial-temporal interaction range for audiovisual event classification, (2) the dependency of audiovisual interaction on auditory context, and (3) its possible relation to crossmodal attention.

References

Metzger, W. (1934). Psychologische Forschung, 19, 1-60.

Sekuler, R., Sekuler, A. B., & Lau, R. (1997). Nature, 385, 308

- Illusory Flashing Visual Percept Induced by Sound

L. B. Shams, Y. Kamitani, S. Shimojo

Purpose: Various studies have shown the modulation of perceived intensity, detectability, spatial and temporal localization of visual stimuli by an accessory auditory stimulus (AAS). AAS is an auditory stimulus that is presented in close temporal proximity of the visual stimulus and which is not to be responded to. We investigated whether the visual percept itself can be modified by such auditory stimulation.

Methods: In each trial, a disk is flashed for 13.3ms in the center of a computer screen (where the subjects fixate). In one condition, the flash is accompanied by a brief sound stimulus that consists of 1 to 3 beeps (with the number and pitch of the beeps randomized across trials), and in another condition, the visual stimulus is not accompanied by any auditory signal. The subjects’ task is to judge the number of flashes displayed on the screen in each trial.

Results: Although the visual stimulus is identical across all trials (a single flash), the percept of the visual stimulus varies drastically across trials. Subjects perceive the single flash as more than one flash in the condition where the flash is accompanied with auditory beeps, and not otherwise. In other words, the sound beeps induce the perception of "visual beeps." Moreover, the number of flashes perceived in each trial is correlated significantly with the number of beeps in the same trial. A single flash is reported in trials with single beep. The results are robust to many parameters namely the duration of the visual flash, the flashing visual pattern, the size of the visual pattern, etc. and spatial concordance between the auditory and visual stimuli is not necessary.

Conclusion: AAS can alter the visual percept qualitatively and significantly. The observed illusory flash effect does not seem to be due to general attentional enhancement caused by auditory stimulation, as there is no illusory flash elicited by a single beep. The illusion does not appear to be a result of eye movements, as the effect is stronger with shorter flash durations, persists with very large disk size, and degrades with decrease in disk contrast. The observed illusion (as well as its non-requirement of spatial concordance between the auditory and visual stimuli) can be explained based on prior behavioral findings relating the audio-visual sensory interactions.

- Sound-induced Visual "Rabbit"

Y. Kamitani & S. Shimojo

Purpose: We previously reported that a single visual flash presented with multiple beeps with short intervals appears to be multiple flashes (Shams, Kamitani, & Shimojo, Nature 2000). Do the beeps produce mere impression of brightness fluctuation, or rather independent visual tokens? To demonstrate that the illusory flashes can be perceived independently at different spatial locations, a visual apparent motion display was combined with beeps.

Methods: Two vertical bars (13 ms duration each) were flashed 3 deg horizontally apart with an interval of 106 ms, creating clear apparent motion. Each bar was accompanied by a beep (10 ms duration, simultaneous onset with the bar). Another beep was presented at a various timing between the flashes/beeps. In a condition without sound, a real additional bar was flashed at an inbetween timing at the same position as either of the two bars. Subjects reported the perceived location of the illusory bar associated with the second beep (if any), or that of the additional real bar. The direction of apparent motion was randomized across trials.

Results: All subjects (3) reported that an illusory bar was perceived with the second beep at a location between the real bars (difference from the real bars, p < .05). This is analogous to the cutaneous "rabbit" illusion where trains of successive cutaneous pulses delivered at a few widely separated locations produce sensations at many inbetween points. The illusory bar appeared closer to the first (second) bar, as the second beep was presented temporally closer to the first (third) beep. The perceived location of the additional real bar was not significantly different from the actual location, thus purely visual "rabbit" was not observed.

Conclusion: The sound-induced visual flashing creates visual tokens that can be spatially displaced, indicating visual proper, as opposed to cognitive, alteration, which nontheless is uniquely induced by sound.